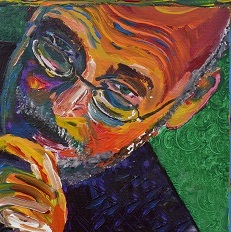

The hostile hospitalist

Dr. Oscar Adversum is not happy about anything, but especially not the night shift.

If you are hoping for an uplifting column to start the New Year, read no further. No, I really mean read no further, because this isn't it.

Dr. Oscar Adversum was not happy as he prepared for a night shift at the hospital. He was feeling irritable, crabby, and just a little bit nervous about the workload and lack of sleep. He was also ill-tempered at the thought that he'd have to adjust to shift work. He was 40—way too old to be working nights. In the hospital at night, he'd be no more than a glorified intern. At least the pay was better, though there were no admission service caps.

His coffeemaker was broken, and he was out of bread. He stuffed some only slightly rancid bologna and a brownish slice of cheese in his mouth as he headed out the door into the twilight. The front tire of his old beater was low again. He hated this old car, but he wasn't about to buy new tires or change the oil. He'd drive it till it died on the side of the road—bald tires, belching exhaust, drooping headlights, and all. The only time he liked the car was when he cut off a Mercedes on the highway or grabbed a parking spot from a Porsche.

At the hospital, he pushed his way onto a crowded elevator and then was unhappy that it seemed to stop on every floor. A passing nurse waved, but he walked by with only a grunt. The PA who would be working with him that night smiled and said she hoped it would be a quiet one. Dr. Adversum snarled at her that the chance of that happening now was sunk because she had said it, so thanks for nothing. He grimaced at the thought of check-out rounds. He didn't want to hear all the details, just the minimum of information. Even the basics he did not like. Why did that patient need him to check a CBC? Why did he have to meet with that family? How were there already two admissions waiting for him? This was utterly ridiculous.

As the night proceeded he got more admissions. He argued with the ED team over whether a patient should go the ICU or his ward. He complained to radiology that their turnaround time was too slow. He disputed the laboratory's claim that a TSH couldn't be added to the bloodwork he had already had ordered. He insisted that orthopedics, neurology, and urology take their own darn admissions.

The worst came when at 5 a.m. he had his eighth admission of the night—abdominal pain. It might be appendicitis, pancreatitis, or ischemic bowel. He would not accept the patient without a CBC and a lactate and an amylase. The white count was normal. He demanded the ED do a CT or an ultrasound before he would accept. There was a possibility of diverticulitis. He wanted a surgery consult. He demanded it!

He walked out of the ED feeling mildly victorious but still grumpy. The ED team and the surgeon were glad to see him leave. The mood lightened considerably once he was gone.

As he left the hospital at the end of his shift, he was arguing on the phone with his date for New Year's Eve. She was canceling because she just didn't like his attitude. As he launched into a tirade of gratuitous profanity and obscenities, he stepped into the parking lot without looking and was hit by an ambulance!

Dr. Adversum survived due to the hard work of the emergency department team who stabilized him, the surgeon who removed his ruptured spleen, the orthopedist who set his fractured humerus, the neurologist who treated his seizures, and the nurse who hung his meds and changed his dressing, as well as the efforts of the phlebotomists and technicians.

Two weeks after the accident, they were ready to extubate him. The critical care physician had turned down his sedation. Several of his colleagues were standing in the hallway watching. As he woke, the PA he had worked with on his last shift sat by him and explained what had happened, how everyone had pulled together to save him and they were going to extubate in just a moment. Dr. Adversum had time to reflect. Maybe this was a chance to live differently, to honor and respect his colleagues.

The MICU consultant pulled the endotracheal tube and the respiratory therapist suctioned. Dr. Adversum coughed twice and looked at the clinicians who had worked so hard for him over the last two weeks. He grimaced and snarled that it had taken too damn long to get him off the vent! Now he was feeling better.