Rounding with the Bard

Shakespeare's words apply to hospital medicine, a fictional physician finds.

Rushing to work in the morning, John Hall, MD, wished he had not spent so much time looking at videos on his phone. Now he was starting his shift in the hole and he wondered how he would make it through a very busy day.

Dr. Hall quickly scanned his service list, and several patients stood out: a young woman with metastatic melanoma, another with an unusual inflammatory arthritis, a colleague dying of pancreatic cancer, an alcoholic patient in severe denial, and a VIP who had fired all of the other hospitalists. Dr. Hall thought of many other patients who were in the hospital but knew he needed to focus on his own service.

But before he could even get started, he was called to the emergency department. A patient, Mr. Bacon, had arrived with mild dyspnea but seemed to be speaking quite easily.

Too often patients come to the emergency department expecting hospitalization. But not all of them—Mr. Bacon only wanted a nebulizer treatment and hoped to avoid becoming an inpatient.

But the ED doctor was unrelenting; Mr. Bacon would be on Dr. Hall's service overnight.

Dr. Hall headed back to the ward. In the first room, which smelled distinctly of anaerobes, he found a patient sitting on the floor with two nurses nearby. He had been admitted with a diabetic foot ulcer and perhaps gas gangrene. He had had a hypotensive episode and near-syncope on the way to get a scan.

Most likely it was hypotension, but Dr. Hall thought it best to rule out an arrhythmia—easy enough to do a quick check.

Meanwhile, Dr. Hall's pager had gone off twice with messages from the nurses dealing with the VIP patient. He had presented with chronic fatigue and depression but was sure he had a dire disease and was taking it out on the staff.

Dr. Hall had no patience for this patient on a busy day. He made his decision and would stand by it.

The next patient on the service was a particularly poignant case. He was a fellow internist who had taught at the medical school for years, and he was dying of pancreatic cancer. They discussed his goals of care. The patient's perspective was succinct.

Dr. Hall next entered the room of a young gardener with confusion, skin lesions, and arthritis. Dr. Hall was proud to have made a tricky diagnosis on this case—sporotrichosis arthritis due to a puncture wound from a rose. The documentation nurse interrupted rounds, pointing out that he inadvertently written altered mental status instead of encephalopathy in the record. Dr. Hall was unapologetic.

The next patient had severe alcoholic hepatitis, spider angiomas, red palms, and macrocytosis but vociferously swore she did not drink. Dr. Hall wondered to himself about the accuracy of her history.

Another patient, who had diabetes, complained about the frequency of glucose checks.

A call came from the administration. Dr. Hall was late for the quality committee meeting, and he had been appointed to lead a project. After attending the meeting, he walked out of the conference room, more confused than ever. His quality project had seemed so simple, to enforce hand hygiene, but despite all efforts, 100% compliance was elusive.

As Dr. Hall walked down the corridor, he passed a resident who had been on overnight and was still there at noon. His advice was simple.

The next patient was an international transfer from Denmark. He had some kind of autoimmune disease with possible pericarditis. Dr. Hall thought he heard an odd noise in the chest, perhaps from pericardial inflammation. A cardiology consultant scoffed at the clinical diagnosis and asked about the level of evidence supporting exam findings in effusions: Was it 2B or not 2B? But when he examined the patient, he heard the distinct evidence.

At discharge rounds, one of Dr. Hall's patients was ready to go, but no home oxygen or home health had been arranged, so he would have to stay another night. Dr. Hall was quite upset at the extended length of stay and risk of hospital-acquired conditions.

The shift was coming to a close. Dr. Hall trudged toward the signout room. His night coverage asked how it had gone today.

With that Dr. Hall left the building, knowing he would be back soon enough for his next shift. He made a small bow to his colleague as he exited.

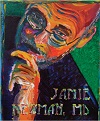

Historical note: Dr. John Hall was Shakespeare's son-in-law, famous for treating patients with poultry larynx, spider webs, and animal excreta.