Canine colloquialisms

These will help anyone who works in the hospital get to the head of the pack.

The sun is scorching its way across the dog days of a Nashville summer. You long for the frozen tundra of Minnesota, to be curled up in your bed with your triad of mutts keeping you warm on a three-dog night.

But instead you've been on call. You rub your feet; you are dog tired. You feel like the hospital is going to the dogs. You have a ridiculous number of meetings today. If you don't want to get dogged, you'd better be prepared because the C-suite can be a dog-eat-dog world.

These and the following “canine colloquialisms” will help anyone who works in the hospital get to the head of the pack.

“I don't have a dog in that race.” You are working in the emergency department, and it is packed. Every room is full, and you're juggling trauma and sepsis, fractures and fevers. In room 12 is a 47-year-old man who is an ED frequent flier. He's drunk again, but this time something's different. His heart rate is elevated and irregular. You scratch your head trying to thing of the doggone diagnosis. Then you realize it's holiday heart. He's in atrial fibrillation. You need to admit him. You ask for a medicine telemetry bed, but the medicine attending calls you and she says she really thinks this sounds like a cardiology admit. The cardiology consultant agrees with your diagnosis but says with withdrawal management, the patient needs to go to medicine. The medicine attending says she is too busy, the cardiologist says they are capped. They are both in your doghouse.

You get them on the phone and tell them to work it out, as you are too swamped and don't care who takes the patient, but you need the room. You tell them both, “I don't care which service. I don't have a dog in that race.”

“That dog won't hunt.” You are in an executive meeting, and your administrator has a great idea. The neurosurgical service line plans to expand, but there are no residents or physician assistants to cover the service at night. He spoke with the surgical administrator, and they feel that the hospitalists can start covering the neurosurgical service calls and admissions overnight, as they really have more than enough capacity to handle this workload without hiring more staff. You look him in the eyes and smile, and say, “Add on another service to cover at night with no more resources? That dog won't hunt.”

“Some dogs have ticks. Some dogs have fleas. Some dogs have ticks and fleas.” Your nurse practitioner is presenting a case to you—an elderly woman admitted with chest pain. She has a long psychiatric history with many admissions over the years with similar symptoms. She is especially agitated this time. It's time to get the haloperidol ready, but first you suggest ordering an EKG to check the QT interval. The EKG shows a STEMI in progress. It's a lesson to be learned. You look at your colleague and explain that just because a patient has psychiatric disease, it doesn't mean she can't have a medical condition as well. It's best not to jump to conclusions and premature closure. You tell her, “Some dogs have ticks. Some dogs have fleas. Some dogs have ticks and fleas.”

“You can't teach an old dog new tricks.” You're a balding but energetic hospitalist more aged than you like to admit. You've adapted to technology—you can place an order in CPOE, and you even have a Twitter account. But now they are hitting you with one change after another. Your handlers have purchased a new electronic health record and have taken away dictation privileges. Speech recognition or typing your documents is your only option. You hold the speech recognition microphone in your hand. It looks like one of your kid's game controls. You look at the pages of instructions and shudder. You are too young to retire, but maybe too old to give up your beloved dictation. One of your colleagues walks by, smirks at your obvious discomfort, and says, “I guess you can't teach old dogs new tricks.” But you only snarl, and with dogged determination you master the system. Sometimes the dog just isn't as old as it looks.

“I've got to see a man about a dog.” The patient's wife has been dogging your footsteps all day. You've had three family conferences this week and spend an SH4's worth of time in the room every day. Still she is a veritable cascade of questions. She is a black hole sucking all your energy into the room. Your shift is over and you're headed down the hall thinking of home. Suddenly she lunges from the room with a pad full of scribbled questions that she has already asked you four times today. She begins to talk to you, but you strategically speed up. As you walk by, you turn your head, smile, and tell her, “Sorry, I've got to see a man about a dog.”

You finish your shift and the sky is dark. The heavens open up; of course, it's raining cats and dogs. But while you wait and contemplate a drenching, the sky begins to clear. Every dog must have its day.

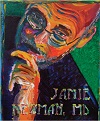

Note: Special thanks to Harvey Bowles, MD, and Josh Eickstaedt, MD, ACP Member, for their contributions to this column.