Dumb luck

Rounds went very smoothly, until we got to Mr. Fibonacci.

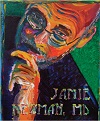

I woke up feeling like a lucky man. I loved my job and my family, the sun was shining, and when I weighed myself I had crossed the fifty-pounds-lost mark. I went to my closet and pulled out a box of my oldest clothes. I'd gone from a 40 waist down to a 34, and today I'd try an old pair of 32s. In the box was a faded pair of chinos that triggered a lot of happy memories as I squeezed into them. I had worn these pants when my kids were little, when all it took to make them happy was pulling an old oversized coin, which I'd picked up somewhere in my travels, from behind their ears. Today I'd wear them to work.

The sun was shining, so I put the top down on my convertible. I made every traffic light and grabbed a primo spot in the doctors' lot. It was such a beautiful day I decided to leave my roof down. I pulled up my census list. There had been no overnight admissions, the service list was low, and I had a solid physician assistant that day. Aside from Mr. Fibonacci in 5-813, all the patients were low impact, low drama. I felt very fortunate indeed.

Rounds went very smoothly, until we got to Mr. Fibonacci. He was a wizened, weather-beaten prune of a man. And he had a personality to match. He was demanding, uncooperative, and vituperative. He had been admitted with abdominal pain after eating what sounded like a roadkill meal of stewed goat meat. He was homeless; the social worker thought he might be living under a bridge. We had run at least 13 imaging studies on him before we determined his pain and diarrhea were caused by Campylobacter.

He'd been clear to leave medically for days but had refused, saying that if we threw him out we'd have to face the cost. Whatever that meant. We'd given him a HINN letter to notify him Medicare would not cover further hospitalization, and all he did was shrug. He'd sit all day playing solitaire, eating hospital food, and watching TV.

Today was the day. I was going to make him leave. I went in with the team: my PA, social worker, and hospital security. In no uncertain terms, I told him the holiday was over. We could get him a bed in a homeless shelter and enough medication to treat his infection. He snarled at me. An actual snarl. I'd had enough. I told him we would be disconnecting the television. His face turned a deep shade of red. He stared at me with an evil grimace and began to mutter in an odd dialect. He pointed two fingers at me and let loose a cackling laugh.

The security guard, 6’3″ of packed-on muscle, turned pale and ran from the room, muttering “malocchio” under his breath. The evil eye. But I didn't believe in curses, and I wasn't intimidated.

I walked out and went to the computer to sign the discharge order, but for some reason, my password wouldn't work. The network was down. My pager went off with an ED admission. I looked out the window and the sky had grown cloudy and foreboding. I thought about my car with the roof down. My pager went off again—this time a unit transfer.

I pushed the elevator button, and when it finally came, it was too full to squeeze on. I ran for the stairs as my pager went off again—another admission. There was a repairman painting in the stairway and I ducked beneath his ladder and took the stairs two at a time. I ran out the alley door to the parking lot, startling a cat that had been sitting by the dumpster, and tripped over a large crack in the sidewalk. I got to my car as the drops started to fall, only to realize I had run out without my car keys. I ran back to the side door, but then I noticed I also had left my wallet in my bag upstairs and could not access the card reader. I ran to the front of the hospital and up the five flights of stairs.

My pager went off again. It was a deluge of admissions. I went into the work room to get my coat and found the electronic medical record was still down. And my pager went off again.

I ran back to Mr. Fibonacci's room. He sat there maniacally laughing as the lightning tore apart the sky. I had no idea what to do. I shoved my hands in my pockets as I tried to think of an answer. I couldn't believe he had cursed me, but it was hard to doubt the sudden turn of events. And then I felt something in my pocket. I couldn't believe it was there.

I leaned towards the vile little man, reached toward the side of his head, pulled my special coin from behind his ear, and slapped it on his bedside table. I told him to use it to buy himself a hot meal after he left the hospital.

As I walked from the room, I looked out the window. It looked like the sky was clearing. The record system came back online, and the admissions turned out to be for the neurology service. As I placed the discharge order, I thought to myself that I was a lucky man.